I had an unusual call with my grandfather a few days ago. Unusual because we usually don’t talk long. Just a minute or two. This time was different. We were talking about the state of things and it was good hearing from him. To hand him my fears and hear no soft words in response. He did not delude me with ideas of progress. Let him tell it, things are largely the same. It must be said that there are key ways that things are different but I understand his point. That my despair is ancestral and shared and nothing new. It got me out of my own head for a while at least, which is more than I can say for my various feeds. He also told me to save my money because I’m going to need it. Anyway. We’re reading Black Marxism! I’m excited about it. I know I promised we’d kick things off in January but the top of this year was brutal so I hope y’all are okay with starting things in February. That feels right, anyway. As far as reading schedule, I’m thinking one chapter a month, which allows us to sit in the work collectively and discuss and digest all the ideas that might emerge without rushing to the next concept. There are 12 chapters so that puts us at December/January 2026 for the endpoint—lots of time for us to live with this text.

Before I started working on this guide I asked the subscriber chat about the things that might be helpful as we navigate the text. The first request was that I offer tips on how to annotate so I figured we’d start there before jumping into a summary of the introductory sections and some analysis on the book’s intention. There’s about 40 pages of prefaces and forewords which are filled with rich (read: dense) analysis about Black Marxism and its impact 40+ years after its release. It’s tempting to skip these and jump into the first chapter, but I promise it’s worthwhile. It’s an opportunity to adjust to the academic tone of the work by reading both Cedric Robinson directly, as well as scholars and former students who deeply understand his work. Someone else (hi Cheryl!) asked for discussion questions, so I’ll pose a handful at the bottom so we can discuss the reading in the comments. Another note, some of the mentioned texts are old and available for free. Where that’s linked, I made a notation using an asterisk (*).

How to Read Black Marxism

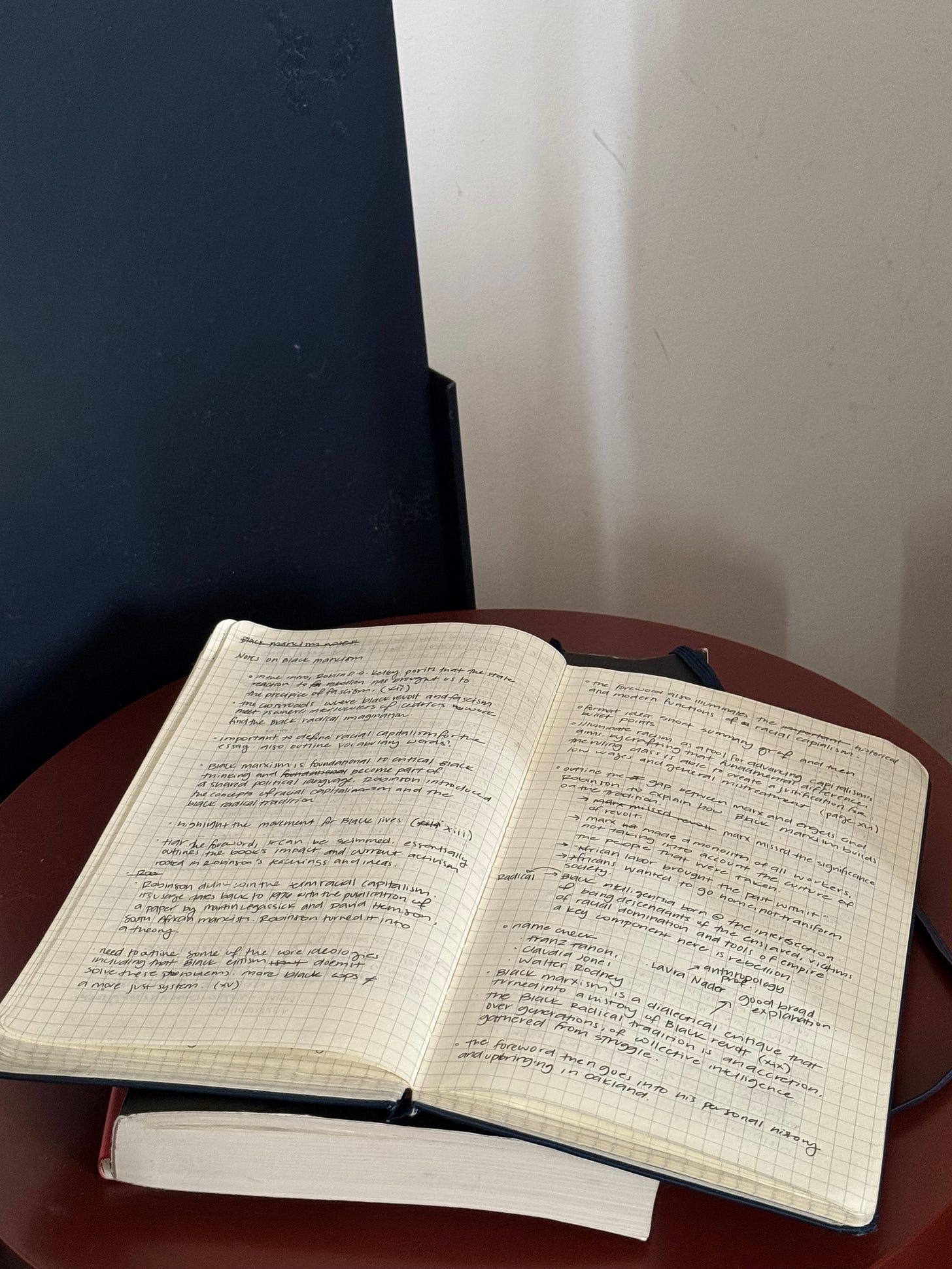

My overarching advice for reading Black Marxism is to go slow. I read everything three times, and it wasn’t until the second read that things started to gel. You might need to reread more or less—the goal here is comprehension so whatever it takes to get there works.

Goals for the first read

The first read is for familiarizing yourself. During this first pass, I would take notes of anything you don’t understand, words you don’t recognize, concepts you’re curious about. For me, this looked like keeping a running tab of vocab words (I looked up accretion, for example) and using mini post-it notes (I use these) to write out any questions or thoughts that come up in real time. It’s also a good opportunity to get used to the writing style and making note of any passages that stand out or excite you.

Goals for the second read

The second pass is for understanding what the paragraphs are trying to say. This is when I transition to notetaking, writing out the key points of each section. I use a Moleskine but any notebook or pad works.

Goals for the third read

The third pass is for full comprehension. By that I mean you understand the gist of the reading and can explain the concepts in relatively plain language. This is also the stage for analyzing and drawing connections. At this stage I like to reread my handwritten notes and then type them up (this helps me with comprehension). On the third read, I felt my opinions start to take shape and I was able to start synthesizing. For example, rereading the intro sent me down a Roman Empire rabbit hole and had me going off about the enduring myth of whiteness. It’s also a good time to start talking to other people about what you’re thinking and seeing, though I think discussion is worthwhile at every step. Think of the comments and chat as a space for navigating all steps of the reading process—I’ll jump in with commentary and clarification where I can and hopefully others will too.

An Analysis (pg. xi-5)

Black Marxism opens with an examination of two seemingly opposing forces: Marxism, an economic and social philosophy that examines the relationship between the laborer and the ruling class, and the Black Radical Tradition, defined by Cedric Robinson as “an accretion, over generations, of collective intelligence gathered from struggle,” (xxx). In that juxtaposition emerges the political theory of Black Marxism, which crafts a new interpretation of the modern world using Black resistance as a framework. As an undertaking it’s incredibly brave. Cedric Robinson was willing to explore this line of thinking knowing that there might not be a neat answer, let alone a cogent one. It’s this curiosity and courage that I hope guides everyone’s critical inquiry—allowing the process to reveal the purpose of the work rather than imposing the work with prescribed ideas.

The book was published in 1983 to little fanfare. It picked up steam as the years went on, eventually becoming a seminal work so important it was reissued in 2000 and then again in 2020 against the backdrop of the racial uprisings, the latest preface asking why Black Marxism? Why now? Robin D.G. Kelley, a historian and professor at UCLA wrote said foreword during that fateful summer, a time when collective experience offered a portal into a new world, one that shimmered with the legacy of the Black Radical Tradition, Robinson’s ideas made concrete. George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were murdered and millions took to the streets in protest. Abolitionists made many demands. Five years on we know none of them were met.

In the preface, Kelley introduces Black Marxism’s key concepts: racial capitalism and the Black Radical Tradition. Robinson argues that capitalism inherited racism rather than birthing it. Racialism—or racism—was already present in Western feudal societies, with the first racialized subjects being ethnic subgroups (Irish, Jews, Roma, Slavs, etc.). When feudalism—a system where the monarchy dispenses land to the nobility and peasants work and live on the land in exchange for labor and a portion of their crop (think sharecropping) gave way to capitalism, Robinson argues that feudalism’s values didn’t evaporate but rather evolved. Marx posits that capitalism is the negation, or contradiction, of feudalism. He views the European proletariat as a universal subject birthed by the invention of capitalism. Robinson disagrees, theorizing that this was a messier endeavor, where the proletariat did not become some unified, homogenized force but rather a fractured, racialized one. This is the environment that birthed racial capitalism, a system “dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism, and genocide,” to achieve its aim of endless growth and expansion. When this system collided with African people and enslavement, which had a long history of revolt, it birthed the Black Radical tradition.

Marx does not account for cultural difference, an element Robinson says is important for the success of capitalism in the nineteenth century (xv). He uses the colonization of Irish people as an example, noting that colonialism shaped the way English people felt toward them. These attitudes transcend class, and gave the English bourgeoisie the framework to justify low wages and mistreatment without pushback from the working class. This point is an important one, because as I see the dialogue move from antiracism to class consciousness, it’s essential to be mindful of the relationship between the two. Racism doesn’t evaporate as we move through social classes but rather can be used as a tool by the capitalist and middle classes to conceal the mistreatment of everyone. This, says Kelley, explains why white workers have failed to align with non-white folks against capitalism in a sustained way. That isn’t to say there haven’t been moments of genuine solidarity, but that the racial stories embedded in our society have fractured the proletariat to prevent permanent change.

In addition to underestimating racial ideology, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels conflate the English working class with the rest of the world. By focusing primarily on capitalist development in Western Europe, and leaving out the plantations, which were sites of consistent resistance and revolt and made up the majority of the non-industrial labor force and produced enormous amounts of wealth, Marxism effectively ignores it. We’ll get there later, but this ends up shaping the attitudes of modern Marxists and accounts for why many Black radicals started with Marxism and later moved away from or critiqued the theory. These revolts were also often led by women, who have always been integral to the architecture of the Black freedom movement (see: Pauli Murray, Septima Clark, Fannie Lou Hamer…the list goes on). These early efforts of revolt were rooted in going home, as Africans had little interest in Western society and the system that kept them enslaved. Over time, Black labor was folded into the social structure, which eventually gave way to the “native bourgeoisie,” Black intellectuals who had access to the dominant structure. This is inherently contradictory—to be both the descendant of the enslaved and have access to empire. That tension eventually produced rebels, thinkers and artists who Kelley refers to as the radical Black intelligentsia.

The last section of Kelley’s foreword offers a glimpse into Robinson’s life—his upbringing in West Oakland, California, his time spent in the Afro-American Association, gatherings where he politicked with future leaders of the Black Panther Party and, funnily enough, Kamala Harris’s mom Shyamala Gopalan. There was a life-changing trip to Zimbabwe where he witnessed American imperialism up close, a chance meeting with his future wife while working as a probation officer. After that, post-graduate study and a stint at SUNY Binghamton, a sabbatical in England, and finally a director role at UC Santa Barbara. In the midst of that he wrote many essays about his experiences and the theories that emerged from it like “Fascism and the Intersections of Capitalism, Racialism, and Historical Consciousness”. Somewhere in there he wrote this seminal text, which offers language and framing for understanding the future, present, and past. He was as much a product of the Black Radical Tradition as a chronicler of it and had a sharp understanding of the way life and politic intersect.

The second preface, written by author Damien Sojoyner and professor and author Tiffany Willoughby-Herard offers more insight to Robinson the professor. Willoughby-Herard and Sojoyner are former students, and this section outlines the practical strategies and frameworks Robinson employed as well as how his academic descendants carry his lessons into their own work. Of all the prefaces, this one is the most optional, but still worth the read. It’s insightful and moving and helpful for understanding Robinson more fully.

The third preface is written by Kelley for the 2000 edition. This is the last time we’ll hear from anyone other than Robinson—the final opportunity to engage with someone else’s interpretation of the work. After this, the book gives way to Robinson’s thinking. That is to say all this is the warm up—a good opportunity to get acclimated. This section digs deeper into the philosophical ideas underpinning Black Marxism’s critique, examining the scholarship of Marx and Engels and offering context for where it falls short. Here Kelley reiterates the ways Marx’s theories fail to account for factors like race, gender, and culture, illuminating the various forces that “constricted” his imagination. His view of slaves, for example, was informed by Aristotle’s attitude. Aristotle believed slavery to be necessary for the self-sufficiency of the population and did not think of them as subjects worth examining. They were on the margins, far from his critical inquiry.

Marx did not have the same attitude as Aristotle toward slavery—he hated it—but his hatred did not result in viewing enslaved people as human. He believed slavery was a “precapitalist, ancient mode of production, which disqualified them from historical and political agency in the modern world (xiix).” What stood out to me about this is that Marx was writing in the late nineteenth century and was fully aware—and wrote about—slavery but resisted creating a comparison between the European labor force (the proletariat) and the enslaved people. Stephanie Smallwood writes about this compellingly for Boston Review: “Marx’s failure to subject slavery to historical analysis led him away from an obvious interpretive conclusion: that slave-trading was analogous to the capitalist labor market because it gave birth to the capitalist mode of production.” Smallwood argues that this failure has always been the weak point of Marxism, a point previously made by Robinson’s ideological predecessor, the sociologist Oliver Cox, who says that Marx makes secondary what should be at the center—the enslaved person herself. Enslaved people were both a commodity and a population, a fact that eludes Marx and Aristotle and modern Marxists too. Similarly to the British proletariat, who, despite their similarities with Irish workers could still hold racial animus, the same holds true for Marxists who root their theory of class struggle in white people and then superimpose that upon all other populations. Reproducing that hierarchy intellectually, where white struggle is positioned as non-racialized and global, furthers notions of Western and white supremacy, even in the midst of revolution. Kelley then charts the work of Black thinkers like W.E.B. Du Bois, Richard Wright, and C.L.R. James—writers who utilized Marxist ideologies to discuss Black resistance and American history, creating an entirely new field of study and inspiring generations of thinkers.

After the preface, we move to Robinson’s introduction, which provides a roadmap of Black Marxism’s structure and defines key concepts like Marxism and socialism. This section is a must-read because you’ll get used to Robinson’s writing and how he structures an argument. For example, he explains the limitations of Marxism by explaining the big ideas and the key players before moving on to its weak points within the boundaries of its scope and then pivoting to the bigger picture, layering in the context of African history and the slave trade. He’s a teacher through and through and invites us to walk through his thinking by providing all the tools we need to come to the conclusion ourselves.

Some major things happen here that we don’t see in earlier prefaces, like Robinson’s definition of Marxism. He outlines it as the collective effort of three thinkers: Engels, Marx, and V.I. Lenin. Marxism, says Robinson, is the study of capitalist expropriation—the state taking property from the owner for its use or benefit—and exploitation of labor, a theory invented by Engels, expanded with Marx’s “material theory of history,1” and his belief in the inevitability of class struggle, which was later evolved by Lenin’s ideas about imperialism and the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” a transitional phase from a capitalist to a communist society where the state seizes the means of production2 (1). He also introduces the concept of nationalism, a mix of racial sensibility and the interests of the bourgeois (3). Robinson says that nationalism complicated the theories historical materialists have about societal change because nationalism creates a shared belief among the population that transcends class and was adopted by everyone. The implications of this is far-reaching. Not only is Robinson suggesting that the scope of Marxism is insufficient because it doesn’t account for culture and race, but that economics is not the sole producer of culture. It isn’t always about money, honey! The intro also situates Marxist’s localized focus in a global context, citing African influence on European culture prior to slavery. This then lays the groundwork for the advent of the “Negro,” a purposefully ahistorical figure whose primary function is labor. By reintegrating the history of enslaved Africans and rethinking capitalism’s founding structure, he charts a new way to understand the world.

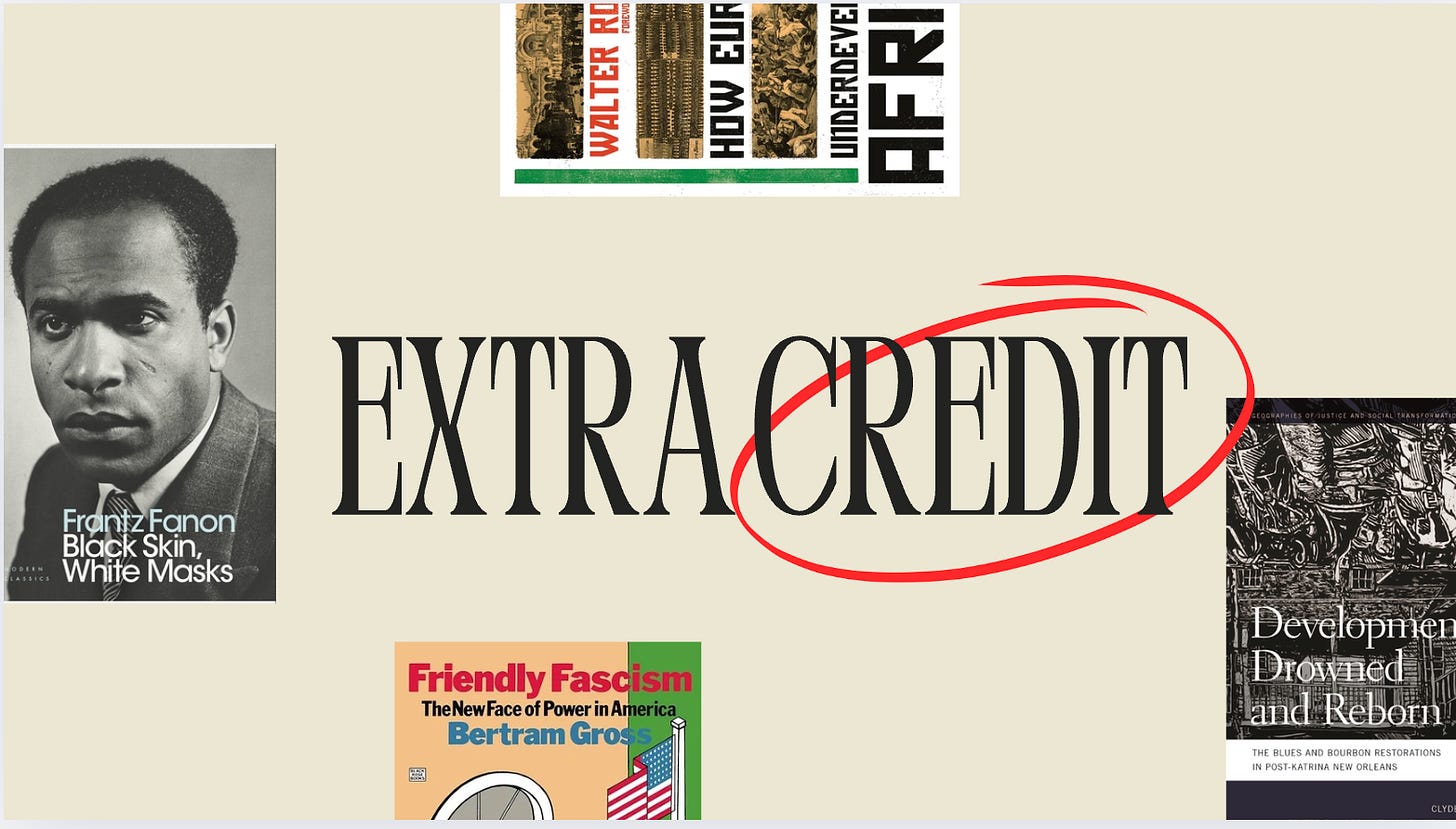

Names to Know (and books to read)

Frantz Fanon - French Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist, philosopher and Marxist hailing from Martinique. His texts are foundational to freedom movements the world over and he’s the author of Black Skin, White Masks, A Dying Colonialism, and The Wretched of the Earth, which made the case for violence as resistance. There’s also a biography—The Rebel's Clinic

The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon—that I have on my shelf and have been meaning to get to.

Claudia Jones - Trinidadian journalist and activist. Her focus was an anti-imperialist coalition, managed by working-class leadership, fueled by the involvement of women. She changed her name to “Jones” to avoid being notable to the surveilling body (bad bitch behavior) and was deported to the UK in 1955. While there she founded the West Indian Gazette and organized a series of indoor carnivals. This would eventually be an influence on Notting Hill Carnival, the second-largest carnival in the world. Her most famous work is "An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!”*, which takes an intersectional approach to Marxism. Introduced the idea of “super-exploitation” of Black women.

Walter Rodney - A Guyanese historian, political activist and academic. His books include How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Decolonial Marxism.

Laura Nader - An anthropology professor who focused on the anthropology of law. Key ideas - “studying up” – i.e. studying the colonizers.

Uri Gordon - anarchist theorist and activist and author of Anarchy Alive! Anti-Authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory

Oliver Cox - A sociologist whose work inspired Robinson’s theory of racial capitalism and critique of Marxism. His most famous work is Caste, Class, and Race* a sociological analysis of race relations in the United States.

Bertram Gross - Political theorist and author of Friendly Fascism: The New Face of Power In America

Siddhant Issar - political theorist

Additional Reading

Race Capitalism Justice (Winter 2017)

Development Drowned and Reborn by Clyde Woods

Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance by Cedric Robinson

A Vision For Black Lives: Policy Demands for Black Power, Freedom, and Justice

Discussion Questions

How does Robinson’s understanding of capitalism conflict with or support ideas you already had?

What about the introductory sections was surprising for you? What did you learn?

Also known as historical materialism, this is the concept that history is driven by economics and that all other structures, like culture and politics are informed by this.

It feels important to note that lots of communist societies tend to get stuck in this phase, and we don’t often hear stories of countries where ownership has been fully reverted to the people.

Thank you all for being here. I’m excited for us to dig in. To close, I’ll leave us with this quote:

“This is struggle to interrupt historical processes leading to catastrophe. These struggles are not doomed, nor are they guaranteed…the forces we face are not as strong as we think. They can be disassembled, though that is easier said than done. In the meantime, we need to be prepared to fight for our collective lives. (xxviii)”

As always. Stay safe, stay vigilant, stay visible. And tell the truth.

Thank you so much for all of this <3

Wow! Thank you so much for this!