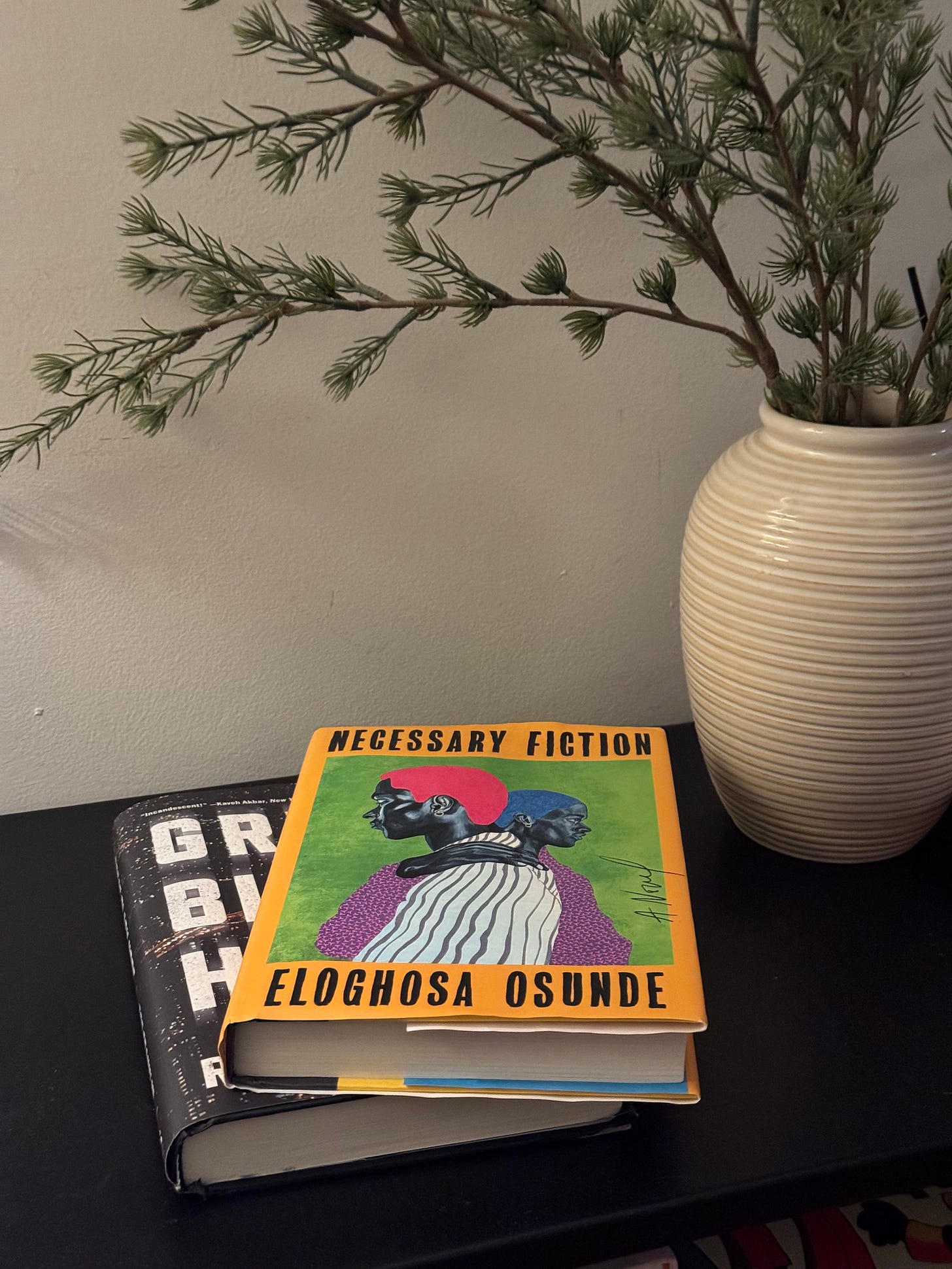

I’ve been thinking about the relationship between intimacy and physical spaces a lot lately. Wondering about what it takes to be vulnerable, to shed the layers of protection, of glamour and sit in whatever constitutes the true self. I’ve been thinking of who gets to be with you there, at your most self-similar, at the very edge of your performance. Who helps to wipe your makeup off at the end of the night. I am a person with many rooms and have given the front-of-house tour to plenty people for reasons no deeper than them giving me a good feeling. But the deeper shit, the stuff that slips when I’m talking out both sides of my mouth—those rooms, the ones I can’t tidy, are reserved for people who call me by nickname and have seen me grow from time. Most met me when I was the new girl from Brooklyn and all I wanted was to be liked and seen and thought of. Some of those people were in the rooms before they had walls, before I knew what it meant to make a home of myself, to draw a boundary somewhere. Every once in a while those rooms get a new visitor but I am the most knowledgeable tour guide, skilled at making mess neat, teasing out the arc and pasting it on the wall for easy navigation. As I get older I wonder what it would look like to have more people join me, to sit in the spaces where I don’t have answers. In reading two novels—Great Black Hope by Rob Franklin and Necessary Fiction by Eloghosa Osunde, I wrestled with the idea.

Great Black Hope is both a grief novel and a meditation on the confounding condition of Blackness, particularly Blackness that holds you psychologically hostage while the body roams free. It follows Smith, a man who spends his days working at a soulless start up and spends his nights at soulless parties with people who shimmer, but only briefly. The novel opens on a fateful weekend when Smith is caught with cocaine and goes up until the sentencing and spends much of its time observing the world Smith has submerged himself in—one of wealth and whiteness—a world he’s now incredibly self-conscious within. His choices are brought into sharp relief when the possession charge threatens to label him a felon, threatening his precarious place in the social order as the son of a well-to-do, upwardly mobile Atlanta family rubbing shoulders with the elite. Smith spends lots of time migrating between physical spaces, from the bustle of a club to the tangled quiet of a shared car with people he barely knows. The novel is constructed in service of this migration, eliminating people and places until it’s just Smith in his apartment, haunted by the specter of his recently deceased roommate, Elle. In the moments when Smith is totally alone, his mind often drifts, resisting present introspection in favor or memory, flashing back to his past, to Elle, the charge looming over his head. The mediations, while precise, often feel like long paths to locked doors. There is little insight into Smith’s wants, and fears. By intellectualizing and analyzing everything with a clinical level of attention, Smith seeks to disappear himself, as if we, the readers, can’t smell the desire on his skin. We are left with the task of paying close attention, to deduce if his fixation amounts to jealousy or admiration or a human mix of both.

I was reading Great Black Hope while also watching Love Island, a show where singles spend a summer in a Fijian villa in the hopes of finding love and, afterward, brand partnerships. In episode 26, the Islanders play a game called Stand On Business, a real-life version ask.fm, where people can submit anonymous messages and then discuss them with the group. At one point, an Islander (Chelley), who’d been upset about the way her friend (Huda) interacted with her partner during a challenge decides to express how she feels. The way she goes about it felt like staring in an uncomfortable looking glass. Rather than locating her feelings within her own hurt and disappointment, she makes a morality play, focusing on principles and hypocrisy rather than how it made her feel. In my experience, this is a good way to win an argument and a bad way to get your needs met. I watched Chelley deny herself emotional resolution in favor of correctness on the basis of consistency, her vulnerability shut behind a door. I have been there more times than feels necessary to recount. It reminded me of Smith at dinner with the two closest people to him, quietly seething because he feels left out witnessing their blossoming connection, opting to say a cutting thing, secretly thrilled when it lands. Neither say the quiet part out loud, the part where they say that they feel hurt or sad or scared, keeping those on the other side of the door at arm’s length. I went through a long period of Smithing, focusing on everyone else and their shortcomings to avoid my own. Anything that was interesting about me not tied to my intellect felt like a wound. Like Smith, I was eventually forced to, unable to hide from the feelings threatening to pull me under. I had to get honest or drown.

On the other end of the spectrum is Necessary Fiction, a novel so open and vulnerable that at times I found myself shrinking away from the character’s earnestness. It is also a grief novel, exploring life on the other side of separations and heartbreak, exploring what one becomes in the absence of noise. It follows a clutch of queer people living in Nigeria, connected through happenstance and luck. They are family, and there’s an emotional nakedness undergirding their interactions, every conversation laced with one-liners that stretch toward life’s biggest questions, like what does it mean to dream under crushing weight? What does it take to love someone else? The novel probes and presents varying theses, but the overarching idea is to make friends with oneself, choose a life you can survive, and let at least one person in.

Although it takes place in contemporary Lagos, Necessary Fiction largely occupies the domestic sphere—homes, hotel rooms, and dark corners—concerned with intimacy above all. Franklin’s silence is where Osunde’s voice begins, almost as if the novelists were standing back to back, eyes on separate phenomena. Where Smith, Franklin’s protagonist sees a locked door, Osunde’s characters see an opportunity for connection, portals into the human experience told through discursive trips to the core of their consciousness—the formative memories, the stories they tell to keep themselves whole. These are characters unafraid of being broken open and starting over again, addicted to self-knowing, allergic only to stasis. There’s a certain futility to both, to having unlimited access to yourself and none at all. While reading, I asked myself which I prefer. I’ve existed both ways.

In comparing the two novels I couldn’t tell which one felt more honest, to lie to oneself and not know it or to dive deep and still come out with true things in one hand, rationalizations in the other. There’s a performance in all of it. Smith refuses emotional interiority in favor of the cerebral while Osunde’s characters have mined their personal experiences for a narrative continuity that explains their present circumstances but resists active conflict and accountability. Theirs is intimacy built through offerings and acceptances, witness without judgment. No one is ever upset that you’ve fallen off the face of the earth and into love or feels hurt by a thing you don’t even remember saying. Everyone has had time to process. So I asked myself—is one truer or does it just sound better? What should we aim for? I don’t believe that we are all-knowing, even on the subject of ourselves, and to see characters act with that authority, a brutal agency that requires excising and choosing and hurting other people and be met with snaps and claps and mhms and thank you’s but never tears or protracted silence or pushback feels difficult for me to grasp. In reading it I learned a lot about meeting people where they’re at, about mythmaking, but very little about repair. If anything it’s the opposite. Cut the thing that threatens to kill you or smother you or invalidate you and find something else. Your people are waiting out there, they’ll accept you, love you unconditionally. They’ll get it, it says, this novel is proof.

But what to do with the ones you got? The ones you’re attached to? The ones you want to understand? Do you discard them in search of new friends with better communication skills and windows into themselves or do you lock all the doors and suffer? Is there something in between? How do you decide who to let in? Is it a feeling you get? Neither novel answers those questions fully, though I don’t know that either intends to. These ended up being the questions I asked myself.

After reading both novels I called Madison M. I had to tell her about the rooms. She immediately understood, because she’d sat in them, allowed me to open the same doors over and over again, praised me when a name changed shape in my mouth. Let my thoughts do the elliptical thing, indulged my curiosity, even when I turned the mirror toward her in order to understand myself. As Morrison said, she is a friend of my mind. She is one of a few who give my pieces back to me in the right order, sorted, prayed over, and consecrated. She’s made friends with my deepest fears, shook hands with my insecurities and told them to come back later, save their sharpest words for the next time we’re on the phone. She helps me see myself, both the version I am and where I want to be. She knows where I’m going, said she’ll meet me there. I don’t hurry, there’s no need for urgency.